Dealing with Scoliosis (And Spinal Surgeons)

If you have the stomach to read all the ways that extra 18th chromosome can affect your child, you will eventually encounter “scoliosis” on the grim list. It’s not a headline condition, like heart defects or central apnoea, but it’s there, part of the small print.

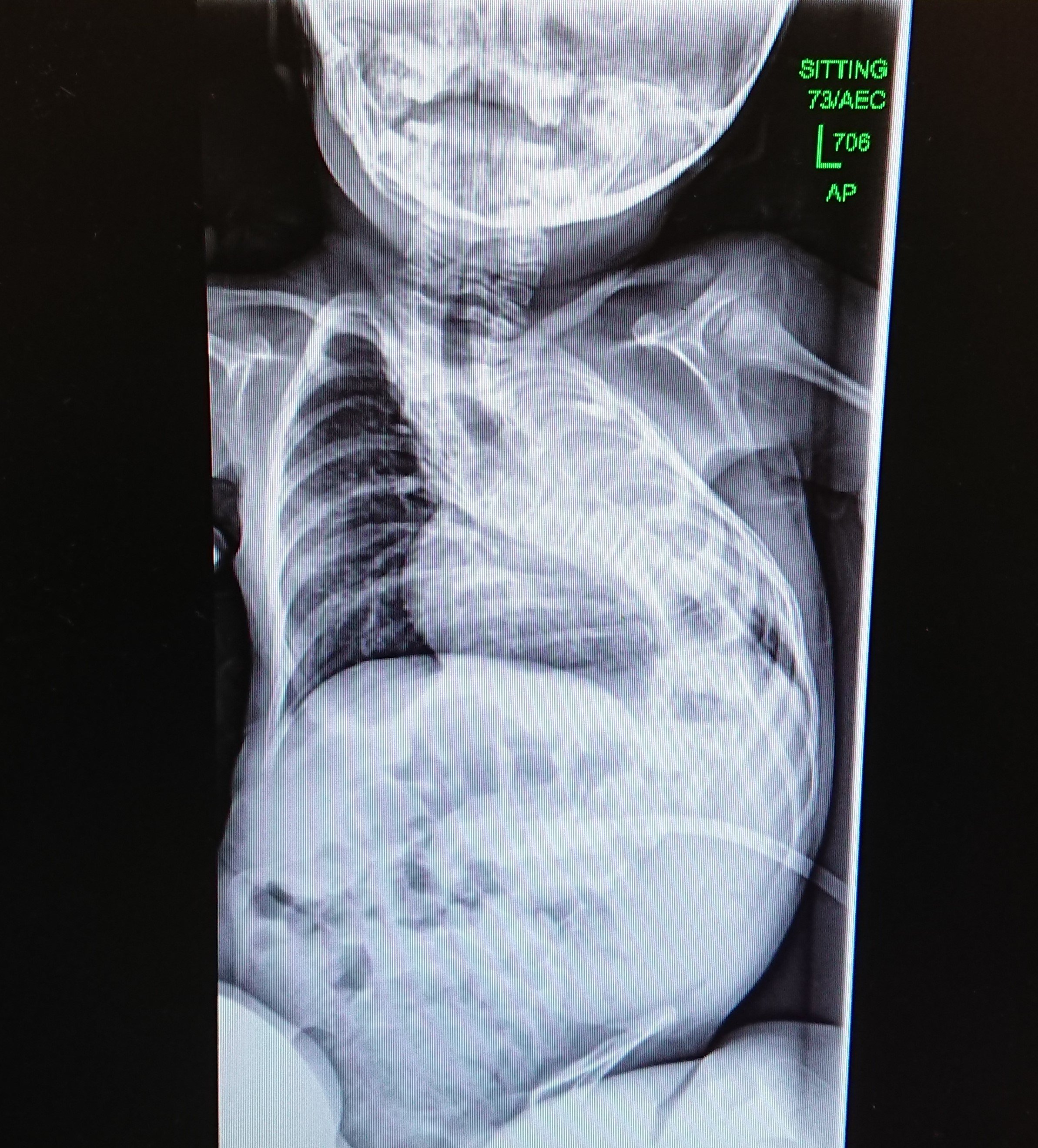

Not all children with Edwards Syndrome have a scoliosis, but I’d estimate about a third of the children I know have. Cali’s scoliosis has been steadily worsening and at aged six and a half it is already over 100 degrees. For the last couple of years, I have been thinking of it as one of her headline conditions, one that is a threat to her survival. It’s been a difficult condition to know what to do about, so I wanted to share our experiences in the hope it might help somebody.

First, let’s have a brief stop at Scoliosis school:

Scoliosis is the term for when the spine twists and curves to the side. There are various types of scoliosis, the most common is ‘idiopathic scoliosis’ which occurs in otherwise healthy teenagers. The kind of scoliosis that affects our children is called ‘syndromic scoliosis’, it is also classified as ‘early onset scoliosis’. The scoliosis is caused by the brain sending signals to the spine to curve, but why this occurs in some syndromes and not others is harder to say, it’s not typically seen in Trisomy 13 for example. Scoliosis is not caused by poor posture or low muscle tone.

It’s hard to predict how a scoliosis will affect your child, in part it will depend on how severe the curve becomes and what other medical conditions your child has. We’ve often been told that the scoliosis in itself is not painful. Cali’s backbone has curved towards her left lung with the result that the lung is now much smaller than her right lung.

Treatments for scoliosis are:

Casting – attempting to hold the curve in place by putting a plaster “jacket” on the infant. This is done under anaesthetic and needs to be recast every few months depending on growth rate.

Bracing: a tight- fitting, removable, brace is worn as much as possible to attempts to hold the back in as straight a position as possible.

Surgical implanting of growing rods: rods are attached to the spine which force the spine to grow straighter, this involves a lengthy operation. The rods are extended every few months, also under anaesthetic, unless ‘Magec Rods’ are used which don’t require surgery to adjust.

Fusion surgery: the spine is made straight or “fused”. Once this has happened growth is restricted, so, where possible, they wait until the child is a teenager.

There are also various measures that Physiotherapists and Occupation Therapists provide, which aim to help your child maintain good posture. These include supportive seating, sleep systems and lycra suits.

Apart from the fusion surgery, none of these treatments will cure the scoliosis. Most of them aim to hold the body in a good position to encourage the spine to grow as straight as possible. Furthermore, there’s very little research on what works for early onset and syndromic curves. This is because very few children in the overall population are affected by these types of scoliosis, and comparing those that are affected is difficult, as the children won’t all have the same syndromes and will also be differing additional medical complexities. Adolescent scoliosis, by comparison, is well-researched and as a result there is a clear treatment plan.

For children with Edwards Syndrome, who are also facing a limited life expectancy, decisions about treatments are even harder to make as parents and professionals have to weigh up whether doing an invasive, possibly dangerous, treatment is going to benefit a child who may not live long enough to reap the benefits of it. Surgeons, who typically oversee the treatment, will often need to consult with other doctors involved in your child’s care to make decisions. This is why the “wait and see” approach is often favoured with children like ours.

Looking back, Cali’s scoliosis was there from birth, she always turned her head in the same direction and had a slightly asymmetrical ribcage. By her second winter there was a noticeable twist in the top of her back, and we were referred to a Spinal Surgeon. Used as we were to parent-centred consultants who gave us plenty of time to answer questions, we didn’t quite know what hit us when the spinal surgeon swept into the room, snapped his fingers at me and said “Edwards Syndrome – tell me about it”, I obediently tried to oblige, stuttering out the facts I thought might be relevant. After a minute or so my time was up and he butted in saying, “If I were you mum, I would be asking me…” then reeled off a few questions which he then proceeded to answer, finishing with “of course, mum knows her child best..” an infuriating platitude given that ‘dad’ was in the room and was every bit as knowledgeable about Cali as ‘mum’. He then swept out of the room for a few minutes to attend to another family he was seeing in tandem, before returning to fill us in on his proposed treatment for Cali, which was; “Let’s wait and see. If she needs it, we can do a fusion when she’s 13”. He concluded the session by saying that if we happened to read something in the Daily Mail that contradicted what he’s said today, or if somebody gave us some advice about Scoliosis in the Clarks Shoe shop that bettered his, then he would be only too happy to talk these suggestions through. Too stunned to respond to this we trudged out, taking our tiny crooked child with us.

This pattern of frustrating meetings continued as Cali’s back worsened. The second time I left the meeting crying and a kind nurse wordlessly handed me a sandwich, she must have seen a few tearful faces leaving these meetings. The third time I took Cali’s physio along with me who gamely suggested that Cali tried a Lycra bodysuit. “Gimmick” he replied, apparently not wanting to waste more than a word on such a suggestion. He had no truck for any of the therapies that physios offered and once said, perhaps in an attempt to outrage even himself, that if we allowed Cali to spend a year hunched crookedly on a saggy beanbag her scoliosis would be no worse than a year spent using supportive seating and a sleep system.

And so, Cali’s curve kept on progressing. Every x-ray showing her backbone shaped more and more like a question mark, pushing up against her poor left lung. It seemed like her body was aptly asking the question – what are we going to do about this? And whenever Cali needed treatment for a respiratory illness it was always the left lung where the virus set up camp, where the air entry was dull, where the crackles were heard. It seemed obvious to us that there was a connection between her scoliosis and her weak left lung.

And yet, despite my belief that Cali’s lung was being slowly rubbed out by her backbone I felt unable to engage with the problem. With every other medical issue Cali had faced I would read about it, network with other parents to find solutions, which I would take to the consultants. I didn’t do this with the scoliosis, I barely read anything. And though Cali had a supportive chair, we quickly gave in and took her out when she wiggled and complained. We didn’t do daily exercises and we said no to sleep systems, as we felt denying her the ability to roll rhythmically was going to make nights even worse. I knew we could be doing more, but we weren’t, and I felt a deep shame and guilt about this. I felt that if Cali died because of her scoliosis it would be our fault. Actually, I felt it would be my fault, my bad mothering; good mothers keep trying, no matter what, good mothers always know what to do. I ended up taking the full weight of responsibility for Cali’s scoliosis onto my own shoulders, so to speak.

What I still struggle to recognise is that I’m not a terrible mother, I was just already at capacity, I was under supported and I felt overwhelmed. Whereas with conditions such as vomiting and sleep apnoea there were solutions, discoverable just by having the determination to keep experimenting. This wasn’t the case with scoliosis, the scoliosis just kept getting worse. The chair and the exercises might buy a little time, but they wouldn’t fix anything. Our only hope was the half promise of a colossal operation should Cali reach adolescence. I couldn’t control the scoliosis like I could control Cali’s other medical conditions, and for me, not being in control of something, on some level was a reminder of death, the thing we can’t control. And so, the scoliosis came to have a powerful and paralysing hold over me as it represented, and I believed would be the cause, of Cali’s death.

Two years ago, I did manage to make some changes. A friend passed me an article about the success of casting in early onset and syndromic scoliosis, this is a link to the summary.

Around this time, I discovered two other children with Edwards Syndrome that had started wearing braces. I contacted the mothers, talking to them helped buoy me up, and C and decided we would ask for a second opinion. The new Spinal Surgeon was as frugal with words and understated as the previous one had been glib and theatrical, but he listened to my suggestion about casting and said he’d speak to Cali’s respiratory consultant about how casting might affect Cali’s breathing. Ultimately however, the thought of repeated anaesthetics, the discomfort for Cali of wearing a brace and the restrictions it would place on two of her favourite activities, swimming and taking baths, led to us rejecting casting in favour of bracing. So, in the summer of 2019, at the age of 5, Cali started wearing a removable back brace.

Cali tolerated the brace well and started sitting for longer periods in her supportive seating. X-rays with the brace on showed her back was much straighter in the brace, and for some months we felt hopeful that the speed her back was twisting might slow down. Unfortunately, the good news was short lived and subsequent x-rays showed that the curve was still progressing rapidly. In February 2020 the spinal surgeon unexpectedly jumped off his quiet fence and told us that the curve was now so bad that he was going to arrange a multi-disciplinary meeting to discuss spinal surgery for Cali.

A few weeks later the UK went into lockdown, which coincided with Cali having a chest infection that needed two back to back courses of antibiotics to shift. After this illness Cali started to drop her sats down as low as 70 at night when she was heavily asleep. We were sure it wasn’t obstructive sleep apnoea this time, and after her heart was checked the only explanation left was that her drive to breathe had dropped, and, well, the scoliosis wasn’t helping. At first, we managed the drops by repositioning her, but increasingly we needed oxygen to bring her sats up again.

Deterioration is a very painful thing to observe and this was the first time I had experienced it with Cali. For me it brought up feelings of powerlessness, depression, anger and sadness. But it also bought up a feeling of softness which allowed me to feel gratitude for all I still had, as well as even greater love for Cali. When I was able to allow my pain to sit alongside my love, I would find myself being the patient and attentive parent that I knew myself to be really, but which was so often derailed by the drudgery and demands of parenting with too little support.

In September the multi-disciplinary meeting finally arrived. We went in feeling nervous, unprepared and unclear about what we wanted the outcome to be.

The meeting turned out to be helpful and cathartic. I was able at last to speak of my worst fears about Cali’s back, and, as is often the case when fears are bought out into the light, they lost some of their power and started to bed themselves down into my mind as things I could accept. The meeting was chaired by a spinal surgeon we hadn’t met before, he was polite, a good listener and explained the facts sensitively and without drama. His only foible, ironically, was an inability to wear his surgical mask correctly for more than a few seconds before having to ping it out of the way and allow his nose to hang out for a bit.

We went into that meeting with the belief that Cali’s scoliosis was the cause of her many chest infections and that sooner or later these would lead to an infection she couldn’t overcome, which was why we thought surgery was needed. All the professionals in the room disagreed with our belief, and with our reasoning for surgery.

The things we learnt in the meeting are as follows:

Cali’s infections may not have been caused by the scoliosis but by that lung being damaged by repeated chest infections, though evidently the scoliosis was not helping. There are children with similar scoliosis who don’t suffer from chest infections. Likewise, there are children without scoliosis that suffer from repeated chest infections.

Doing surgery in the hope of reducing chest infections was not an option. Even with a straight back Cali’s lung would continue to be small and susceptible to infection.

Whilst Cali may survive the operation, the recovery period would be treacherous and full of complications. She would be on PICU for many weeks, susceptible to infection, unable to cough to clear her lungs and so there was a fair chance she wouldn’t survive the recovery.

This was based on her small size, her already poorly functioning lungs and her sleep apnoea.

Whilst Cali’s scoliosis has already gone well beyond the point where they would intervene with a healthy child, she was still comfortable, and sat with straight hips.

There may become a time when Cali’s ribs start rubbing on her hips and this would be incredibly painful. This would be the time to think about surgery.

Conclusion: the risks of operation and recovery was so huge that it should only be done either when Cali’s quality of life was compromised by uncontrollable pain, or when the scoliosis was causing such impact on breathing that it was the only way to try and preserve her life.

When we got to this point a single operation to fuse the spine would be considered. She would have to undergo heart surgery first.

Though in some senses the news was catastrophic I left the meeting feeling at peace. I finally felt I understood enough about Cali’s scoliosis so that I wouldn’t have to worry that there was something I needed to know which I didn’t. I was also sure that the decision not to operate just yet was the right one. Until that meeting I hadn’t felt like Cali’s best interests had ever really been considered, but now I felt they had been. It helped that Cali had been happy and charming during the meeting and had been seen as the wonderful child she is, rather than as a condition that needed consideration.

We left the meeting with a clear instruction from all the professionals in that room – enjoy the now.

I often say to new parents that their child’s body will take it as far as it can. Evidently the right medical interventions and attentive parenting are also important, but ultimately it is down to the cards that the child is dealt. Cali’s cards have been pretty good for a child with Edwards Syndrome, but the scoliosis is beginning to wreak damage on her body; she now often holds her head to one side which is more comfortable for her, and we recently acquired an oxygen concentrator which all too often rumbles and puffs its way through the night. I think her scoliosis might prove to be the full stop on how far Cali’s body can go.

If you are looking for advice, then I would start by suggesting you make sure your spinal surgeon works with children who have early onset scoliosis. Maybe read up on casting. I wonder whether a cast would have helped control Cali’s curve. But I also know that casting or bracing are often not good options; quality of life is immensely important, and not just your child’s, the rest of the family’s too. Do get the supportive seating and try and make stretching and strengthening exercises a fun part of your child’s routine because they will be good for your child in lots of ways. Nursery/school can do the exercises too. If your child likes water, swimming is also good for their back. This winter we have started Cali on a prophylactic dose of antibiotics to help protect her lungs from infection and further damage, this might be an option if your child is already having a lot of chest infections.

And if your child has a scoliosis – don’t despair! I feel bleak about Cali’s future, but who knows? When has the future ever behaved as we expect? Saskia, who I think of as the matriarch of all our British children is aged 29 with full trisomy 18 and a scoliosis. Saskia has journeyed through her 20’s in good health and managed well. Heni, a beautiful soul, lived a happy life with a scoliosis for many years, she died peacefully when she was 21." Our children often amaze us.

As usual I write these blogs partly to help me make sense of my inner world, but also in the sincerest hope that my experience might offer something that feels helpful to another parent or professional. If you have anything to share, please feel free to comment below.

Best wishes, Jay.