Trusting Doctors when your child has Edwards Syndrome

Our dog died this week. Sweet smelly old Eva. She came to us when we lived in Spain and we mollycoddled her obsessively in those pre-children times. She quietly observed our lives for eleven years, rarely asking for much and always tolerant when we needed to bury our sad faces in her warm fur or pick her up to waltz joyfully. She was extra sweet when I was pregnant with Cali, and uneasy when I first came home from hospital without her. From her basket she watched the years with Cali unfold and felt all the emotions that tumbled around the house. In the last year or so she would often position herself next to Cali so she could caress her haunches.

The day before she died Eva fractured a bone in her leg. Under anaesthetic it was discovered that the leg was infested with bone cancer. The vet’s conclusion was that the bone cancer would stop Eva from healing and that nothing more could be done for her. We were asked if she should put Eva down there and then, or if we would like her brought back so we could say goodbye and then have her put down when we were ready.

Through sobs we decided that the best thing for Eva would be for her to slip away whilst under the anaesthetic. This is what happened. I never got to say goodbye. By the time I returned home from work she was buried in our garden.

The next day I realised that I hadn’t thought to question the vet’s prognosis. I’d had complete trust in her experience and integrity. She’d said it was incurable, so it must have been. Cody had asked if there was any point seeking a second opinion, but when she’d said there wasn’t he’d believed her.

I presume we were right to trust her. We didn’t trawl the internet looking for families who’d had the same diagnosis but had found a way of humanely prolonging their dog’s life. Nor did we have a stab at making an alternative diagnosis ourselves. We certainly didn’t wonder if our dog had been a victim of institutionalised discrimination against her breed or condition. And we weren’t left agonising about whether we did enough for her. As I’ve pondered this I’ve been struck by the ease with which we were able to trust a vet we hardly knew as compared to the wariness with which I trust even the best of Cali’s doctors.

Until I had a child with Edwards Syndrome I had a high level of confidence in medical professionals. This trust started to corrode on Cali’s eighth day of life when we were told by a Consultant Neonatologist that any type of resuscitation was inappropriate for our daughter. This announcement was made in spite of the fact that Cali had needed nothing more than an NG tube and some UV lights to ready her for discharge. She was functioning well, breathing and feeding and at that point only her heart condition had been detected. It was a potentially severe heart condition but one that wasn’t yet affecting her (and still isn’t) and which was theoretically fixable. So, given this reasonable bill of health, why was there to be a blanket policy not to resuscitate our child? It was because she had Edwards Syndrome.

When I ventured the opinion that wouldn’t resuscitation be OK if it was to get Cali through a one-off apnoea, the hospice at home nurse, who was also in the room, was called upon to second the neonatologist’s view. She shook her head saying “Resuscitation can be very invasive”. The pair of them half won me over, though in my head I wondered if I would mind my baby being “invaded”, if the outcome was that she lived. But at that moment I was a wreck of a person; exhausted from recent childbirth, from expressing milk eight times daily and from the unspeakable shock and trauma of the last few days. I dully supposed they must know what they were talking about. The only win I achieved in that meeting was the permission to borrow the apnoea alarm Cali had been using, even this was contested, with the consultant quoting research at us that parents find apnoea alarms more anxiety inducing than helpful. I later realised this research referred to parents of premature babies just released from hospital, not parents in our position who just wanted to be present when their child died.

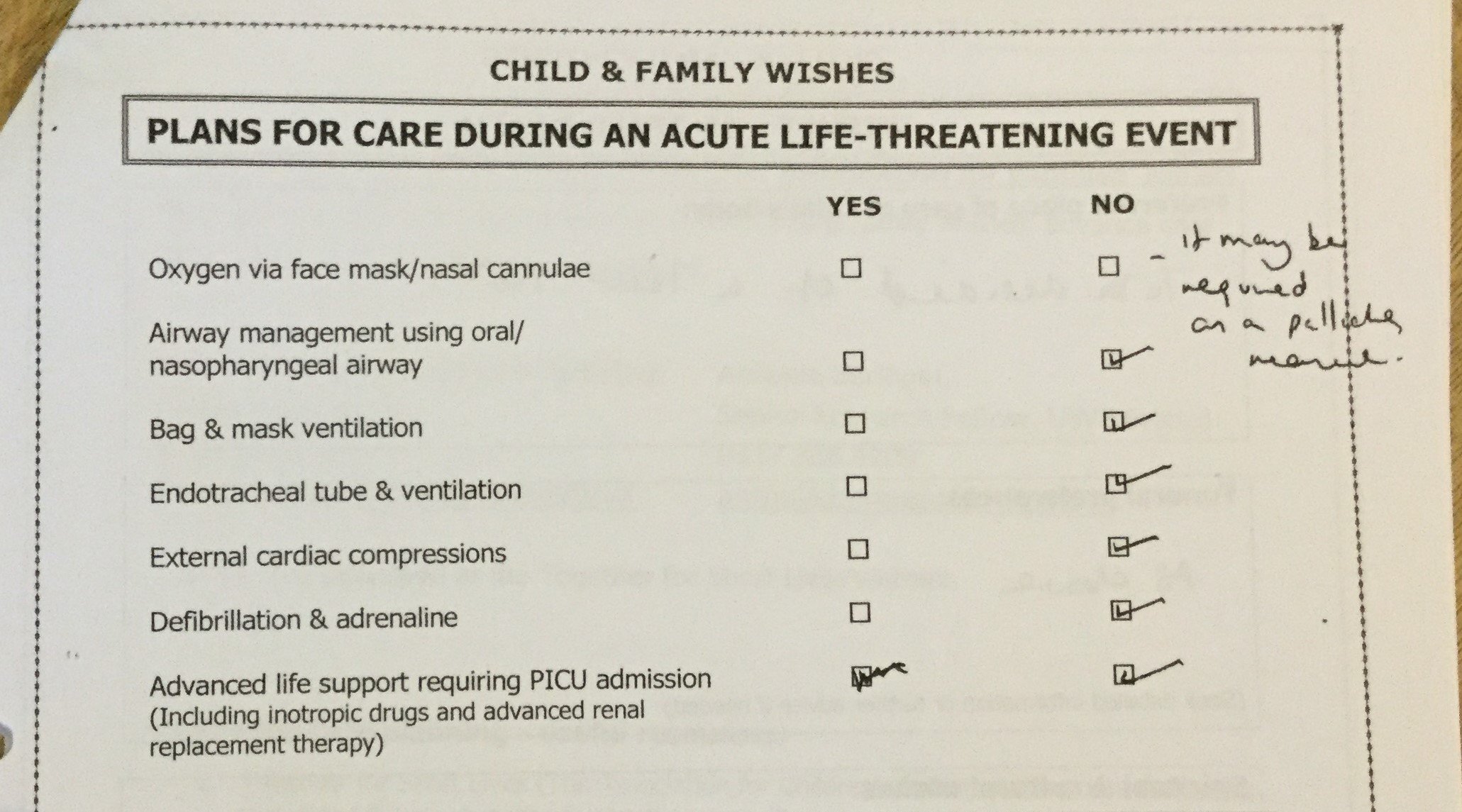

After the meeting the neonatologist wrote out for us our “Wishes document” where he ticked the boxes to decline resuscitation and we signed away Cali’s rights to life. We took our baby back to the room where we were staying and prepared ourselves to go home for “family time”, or put another way, to wait for Cali to die.

I believe that our decision to sign that first ‘wishes’ document was not based on informed consent, neither ourselves, nor actually the doctor advising us, were properly informed about Edwards Syndrome. Part of me doesn’t want to give this doctor too hard a ride as I know he believed he was acting in Cali’s, and maybe our, best interests, however, in my opinion, he was committing a very basic error, which was that he was treating Cali as a syndrome rather than as an individual. Instead of assessing how well she was coping with the syndrome that she had, as the unique being that she was, all he could see was that she had that particular syndrome. And as the overarching medical opinion was that it was not a survivable syndrome, that was enough to make him feel he needed to secure our consent not to resuscitate Cali. The only way she would survive would be if she did it completely on her own.

Is this how doctors normally treat patients? No, normally a patient’s clinical condition is carefully assessed and then treatments are discussed. If a patient’s ability to survive a treatment is questionable, then this will be part of the discussion. It amazes me that we live in a country where a consenting adult with a terminal illness cannot be helped to die, and yet in a small room in a well-regarded children’s hospital a single doctor can make a decision about whether a newborn should be resuscitated.

And in that cloistered world of NICU that this doctor worked in, his decision feels all the more discriminatory when it’s considered that much of his work was spent working on very premature babies, many of whom would come perilously close to death, sometimes repeatedly, in their struggle to survive outside of the womb. Medical intervention for very premature babies is brutal and invasive, but it is, as far as I understand it, the norm to offer full intervention. My point is not that they shouldn’t receive such treatment, but why another baby, also medically fragile and facing an uncertain future, cannot access any treatment. I wonder if the ability to coax and nurture a baby born at 23 weeks through to term is simply more of an accolade for medical science than the ability to give a baby with Edwards Syndrome a few weeks, months or years of life?

The only reason we didn’t blindly let Cali die in that first month or two, when we knew nothing about Edwards Syndrome, was because Cali never came close to death. By the time she needed her first big intervention, which was the placing of a Nasal Pharyngeal Airway at three months, we knew enough about the condition and attitudes toward it, to arrive at hospital armed with suggestions, with a forcefield of cynicism and our fists up, ready for the fight. And Dr H, you wonderful man, you disarmed us straight away by gently saying that you didn’t like to say no to things and let’s see what we can do…

As an adjunct to this, the same Neonatologist who had convinced us to sign Cali’s right to resuscitation away, got wind of this appointment with the respiratory consultant and materialised as we were waiting to be seen, he told us that he’d come to tell us not to “make things too medical”. Quite an effort to go to, he’d had to walk between two hospitals to find us. Presumably this was an indication of how strongly he felt that we shouldn’t pursue treatment for Cali. And yet, when I met him in the street some months later he confessed that he had now changed the way he thought about Edwards Syndrome because of Cali. Hearing this has helped me to continue to push myself to educate medical professionals whenever I encounter them.

My own experiences, and my involvement with the Edwards' and Patau's community, has convinced me that self-fulfilling prophecy has a significant role to play in the death of many babies with Edwards or Patau Syndrome. We see self-fulfilling prophecy occurring prenatally when pregnant mothers with a diagnosis will be offered termination countless times even when they have decided to continue with their pregnancy. They may then be denied additional scans to monitor their babies and the efficiency of the placenta. They may be denied the type of birth that they believe will give their baby the best chance of survival. We also know that once a pre-natal diagnosis is given, parents are often told that their child will not receive lifesaving medical help once they are born. Parents receiving a post-natal diagnosis will often feel compelled to follow the medical professionals lead of minimal or no intervention.

All of this leads to more babies with Edwards and Patau Syndrome dying, a vicious circle of self-fulfilling prophecy. Their deaths are easily absorbed into the high mortality rates of Edwards and Patau Syndrome, as often it’s impossible to say how much of a difference more medical support would have made. But I am convinced that some of those babies could have become surviving children. What is also rarely considered is whether a baby might actually have a mosaic form of the syndrome, which can considerably soften the effects of the condition.

I’m not denying the high mortality rate amongst babies with Edwards and Patau syndrome. However, our babies are individuals and are uniquely affected by their extra chromosomes. All I ask is that our babies are treated according to their clinical condition, and that their lives are seen as being as valuable as any other child’s. As a good friend of mine, whose 8 year old has full Edwards syndrome says, if you asked doctors not to resuscitate your “normal” child when they come into hospital with a treatable condition, the likelihood is that the hospital would contact social services.

In fact, when parents won’t consent to essential treatment for a child, doctors can apply to the courts to override them, or if it’s an emergency ignore their wishes altogether. It really pains me how unlikely it is that any doctor would try and override the wishes of a parent of a child with Edwards or Patau Syndrome if they came into hospital with an easily treatable condition, and the parents then decided they didn’t want appropriate medical intervention.

But it’s not all bad. Not all doctors write off our children. There are babies all over the country that have received the right treatment at the right time. There are also babies and children who have received treatment after a fight, but in time for it to help. The older our children get the more likely it seems that they will be assessed individually rather than syndromically. Attitudes, I believe, are slowly changing; heart surgery sometimes happens, the first British child with full Edwards with a tracheostomy is doing well. These children that have been treated are trail blazing the message that our children are worthy of being medically assessed rather than fatally pigeonholed.

Having a child with Edwards or Patau Syndrome may mean that we find it hard to trust the medical profession. Many of us will have experienced discrimination towards our child at some point. But it’s important that I also say that since that landmark appointment with the Respiratory Consultant, in general, Cali has received exemplary care from the medical profession. That’s with the caveat that she’s never yet fraternised too closely with the grim reaper.

As it is, I feel that I need to understand as much as I can about Cali’s many medical conditions, just in case treatments are being overlooked. I am always on the look out for discrimination. And I force myself to try and educate every last doctor I meet just in case it makes a difference to another child one day. All of this is tiring and so much responsibility. It’s taken the lightness of being able to trust a vet with my dog’s death to understand the heaviness of trying to safeguard my child’s life in a health system that doesn’t always value her existence.

Jay x