How Well Does Your Child Breathe

When Cali was discharged from hospital at ten days of age we knew that babies with Edwards Syndrome often had attacks of central apnoea, which is when the brain fails to tell the body to breathe. This is what we watched nervously for, and why for 18 months Cali had an apnoea probe stuck to her belly like a strange antenna. The probe was then plugged into a box at night and was designed to alarm should the belly stop moving. Indeed, the box would sporadically start squawking, but after a dozen or so dashes to Cali’s cot, only to find her sleeping peacefully through the siren, we learnt to ignore all but its most insistent protestations. Cali, it turned out, wasn’t affected by central apnoea. It took some years before we felt completely able to trust Cali’s brain to take care of her breathing, the belly probe was first swapped for an apnoea mat, but even this was turned off at some point in her third year.

Central apnoea is the thing most new parents will be warned of, but it’s not the only kind of apnoea our children are prone to, as we were to discover. When Cali was 10 weeks old she started finding it hard to sleep for more than a minute or two, especially at the beginning of the night. It was terrible to watch. She’d fall asleep, then after a couple of minutes she’d make a strange noise in her throat, then a few seconds after that she’d jerk herself awake. Then the process would start again.

There are certain episodes from Cali’s first year that have particularly stayed with me, one such episode is the afternoon I realised why Cali was unable to stay asleep. The summer of 2014 was a hot one and the world cup was on. C and his brother were boiling downstairs in their polyester Spain tops glumly watching their country play. I was upstairs in our airless bedroom lying with Cali, watching her cycle through the same distressing pattern: fall asleep, make a noise, jerk awake, repeat. Over and over I watched, I imitated the noise in my throat and I suddenly felt like I understood. I went onto the American Facebook group and read some posts about obstructive sleep apnoea and then posted my own observations. Parents were quick to respond. “Is her body still trying to breathe with no air going in or out?” they asked. I watched some more, I thought it was. Sounds like obstructive sleep apnoea they told me. It should be fixable, they added.

Obstructive sleep apnoea occurs when the muscles in the throat, which naturally relax during sleep, cause the airway to become obstructed. Generally, the body will continue to try and breathe for a few seconds before waking itself up. We later found out that in Cali’s case her low muscle tone was causing the blockage and that she was further limited by having a tiny jaw and small airways which restricted the amount of air she could take in. Obstructive sleep apnoea is a fairly common occurrence in babies with Edwards Syndrome, though this doesn’t seem to be widely known. It’s been theorised that many early deaths might have been misdiagnosed as being caused by central apnoea when it could have been either obstructive apnoea or a mixture of both . This is a tragedy because whilst there’s few options to treat central apnoea, there are treatments for obstructive apnoea.

That moment of deciphering my daughter’s behaviour is one of my first memories of feeling like a proper mother. Good mothers, I believed, understand their babies. They know what they need and are the most important person in their baby’s world. I hadn’t been having this experience with Cali, or not to the extent I thought I should be. I had no idea what was going on with her most of the time and there seemed little that was exclusive to her and me, no sign even that my arms were preferable to anyone else’s. My dogged determination to keep expressing milk was partly founded on the feeling that this was the only thing I could do for her that nobody else could. So, correctly intuiting that Cali had obstructive sleep apnoea felt like I’d finally, in my own eyes, gained a bit of credibility as a mother.

It took some time before we got to see the respiratory consultant who we hoped would help Cali. Those weeks were bitter sweet. Cali was just starting to smile and show endearing glimpses of her personality, but she was struggling to sleep so much that I feared she would die. I remember feeling such rage at her body for not working properly that at times I wanted to shake it because the person that lived inside that body was so precious to me. It was a rage born out of a feeling of impotence. I realised then that it is the things that can’t be made better that cause the most pain.

I’ve written before about our first appointment with the respiratory consultant. It was a defining moment in our life with Cali. This consultant was the first medical professional not to mention her life expectancy, he seemed only to see a medical condition that he believed he could help with. He listened to us and looked briefly at the videos we’d taken of Cali trying to sleep and then agreed with the plausibility of our diagnosis. He patiently endured my somewhat wild suggestions for treatments which I’d harvested from American mums, including tongue reduction, and jaw surgery, never once putting me in my place as novice to his expert. Then he agreed that my most tame suggestion of trying a Nasal Pharyngeal Airway was a good place to start.

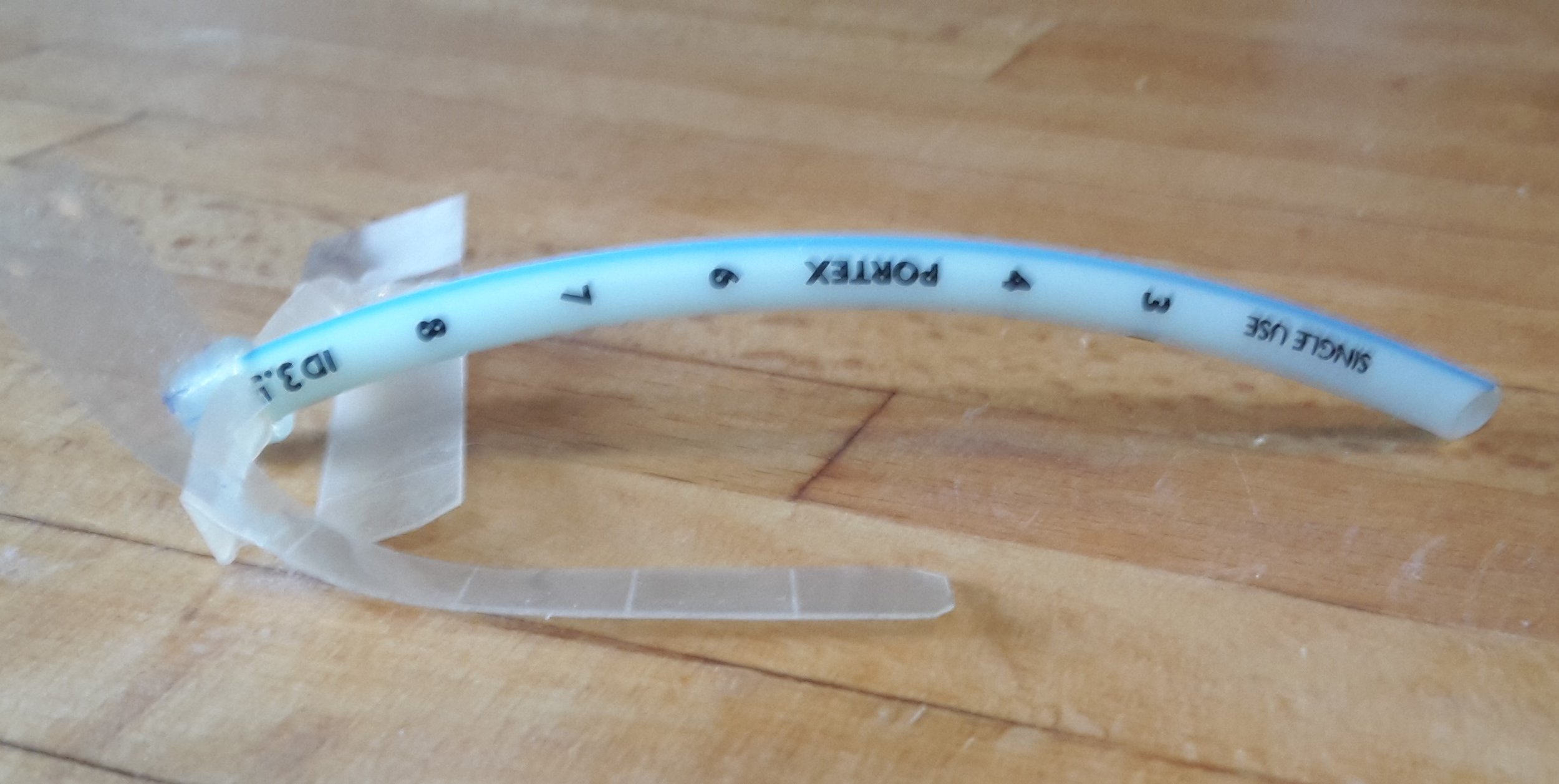

A Nasal Pharyngeal Airway, or NPA, (known as a nasal trumpet in the US) is a short tube that is inserted into one nostril in order to maintain a passageway for the air to flow through. The NPA only works on the upper airway, so our hope was that this was where the obstruction was. The consultant suggested trying the NPA as a way of discovering this, rather than having an intrusive bronchoscopy under anaesthetic.

Shortly after this meeting we did our first home sleep study. This confirmed that when Cali was able to fall asleep she was obstructing recurrently, 30-40 times an hour. Soon after this Cali was admitted to hospital to try and fit an NPA. The summer boiled on and those days in a stifling room in hospital were intense and formative. This was our first admission into hospital with Cali and we started learning the ropes of hospital life and figuring out how to be parents of a medically complex child. We were waking up to the fact that the things we thought we needed to know as new parents were of little importance right now, instead we had to get up to speed on sats monitors and airway anatomy.

The consultant asked one of his trainees to pass the first NPA. This was a terrible decision. The trainee struggled and clearly caused pain to Cali who wailed piteously whilst C and I held her down. It felt horrific, another nightmarish moment where once more I wondered how we could be here, doing this, when we should have been at home riding the normal highs and lows of first time parenthood. Eventually the consultant passed the tube himself and did so easily, but I think we were too traumatised by this point to take any comfort in this. Five years on, it doesn’t feel like too much of a stretch to believe that the difficulties we sometimes still have with passing the airway perhaps started here, witnessing a professional struggling.

Once the haze of trauma had cleared a bit I was appalled at what I saw. The NPA tube is normally used in emergency situations when an airway is needed quickly and comes with a chunk of plastic on the end which I believe is used to attach to oxygen and ensure the tube doesn’t slide into the airway. Our daughter now had a tube sticking out of her nose with a chunk of blue plastic bobbing comically off the end. I couldn’t believe that this could be a genuine solution to the problem. Cali looked freakish. My distress was such that after some time another solution was proposed. They chopped the plastic off and swaddled the end in tape to ensure it didn’t slip into her nostril. Later on they came up with the idea of using a safety pin to stop the tube from sliding into Cali’s nose. And so, with Cali looking like a miserable punk, we settled down for her first night with the NPA in.

The next day the consultant told us that the sleep study showed that Cali sats had stopped dropping every few minutes and that he believed the NPA was going to be beneficial to her. This was the news we were hoping for, but it meant we now had to learn how to manage the NPA for ourselves. This meant learning how to put it in, keep it clean and monitor its effectiveness. Around this point another drama occurred when a hitherto unknown member of staff came in to tell us that using a safety pin to stop the tube from entering the nose was a health and safety hazard which could not be ignored. As I listened to her rant, which included no suggestions on how to remedy the situation, I remember slightly hysterically wanting to point out that as far as I was concerned it was not the health and safety aspects of the safety pin that was alarming me but the aesthetic ones.

Luckily, I’d taken matters into my own hands and been in contact with another mother whose child with Edwards Syndrome also wore an NPA. It would be hard to overstate what a good friend this particular mother has been to me since we made contact in those early days. She’s got three years more experience of mothering a child with Edwards Syndrome than I have, and to me she feels like the older sibling who fights the battles which enable the younger sibling to get an easier ride. Even now I still find myself turning to her whenever anything new comes up for Cali. Since we’d arrived in hospital we’d been exchanging long messages and she’d been answering my every question. She put an example of how she assembled an NPA in the post to the ward, and using this, and the detailed instructions on the GOSH website C crafted an NPA that didn’t rely on safety pins or bits of bobbing blue plastic as safety measures.

Two days later, after we’d both successfully passed the NPA into Cali’s nose and had a crash course in suction, we left the hospital clutching a box of catheters, Cali and an unsubtly bright yellow suction machine that weighed a kilo more than her. Cali’s cheeks were now plastered in tape to keep both NPA and NG tube in place.

It’s hard to put into words the relief I felt when it sank in that Cali was able to sleep without obstructing her airway. Her baseline sats were now steady at 91-93 though she’d still do some big drops during the night. As she has got bigger her sats have continued to improve and now sit at 95-97 with no big drops. Cali started putting on weight at this point and pulled herself onto the lowest centile for a while. Life became even more complicated as we now had to master the intricacies of the tube, but it also felt like a victory over Cali’s malfunctioning body. And a glimmer of hope that we might have some control over the complications that extra chromosome had created. Until then I’d felt at the mercy of Edwards Syndrome, now I felt like I was cautiously in the driving seat.

Living with a child with an NPA

The NPA is a simple and effective solution to obstructive sleep apnoea, but it is also a low-fi bit of kit, rarely used outside of emergency medicine. There are few instructions and nobody local, outside of hospital, is trained to pass it. Even with bountiful help from P and other parents we’ve had to do a lot of figuring out ourselves. C has used his creativity and practical skills to work on the best design for Cali, and has refined the original prototype considerably. We have to figure out when to lengthen the tube, which after 5 years we’re still not confident at doing. At first we kept lengthening it regularly imagining that it was helping, blaming Cali’s insomnia on other problems. One day when Cali was sleeping fitfully in her chair C gently pulled the NPA out by a centimetre and she instantly settled down to deep sleep. That showed us.

Having to wear an NPA puts Cali in a different category of medical complexity. She’s often given an HDU bed when she is in hospital. It also allowed us to get a blue card early as we had to heft that yellow monster of a suction machine around. (Later we discovered the smaller, more discreet Medella Clario). It means people looking after Cali need extra training, and that most of our family members are a dab hand with a catheter. It also means extra stares from people and extra questions and assumptions. Most people assume it is a feeding tube. One well meaning stranger told me that her friend’s son had worn the exact same feeding tube, and “he is fine now”.

Because she’s worn it almost all her life Cali has never objected to wearing her NPA. Once a week she has a day without it to allow her nose to heal where the plastic rubs it. Yet although C and myself feel the benefits of a day without a suction machine or catheters, as well as being able to enjoy Cali’s tapeless face, I always get the sense that she is happy to be reunited with it when it’s passed at the end of the day.

Passing an NPA is not theoretically that difficult. It’s much shorter than an ng tube, but it’s wider. Although between us I imagine we’ve passed that tube more than 200 times I still don’t feel fully confident and always heave a sigh of relief when it’s completed its journey through that mysterious passageway from nostril to voice box. Cali hates having the tube passed and when things don’t go smoothly it makes for a borderline traumatic experience for all concerned. There are often tears (Cali and myself) and vomit (just Cali). I’ve come to realise the difficulties we experience are largely psychological and how much of a difference feeling calm and centred makes.

An NPA is not the only solution to obstructive sleep apnoea. Another approach is to use a form of hi flow respiratory support such as CPAP or Optiflow at night. These both send pressurised air into the airway via a mask. Though we are currently considering CPAP as an alternative, for us a major selling point of the NPA is that we have an easy way to suction out the secretions when Cali has a cold. Likewise, we are also able to suction out the reflux Cali experiences which otherwise will often make her vomit.

For children whose obstruction is not helped by an NPA or hi flow respiratory support, because the floppiness is lower down the airway, a tracheostomy becomes the option. This is a more medically complex step involving a longer stay in hospital and has a bigger impact both on the child and on family life. For example, children with tracheostomies may need care through the night and will not be able to use their voice. The surgery might not be offered easily either. Children with Edwards Syndrome have been refused tracheostomies just as they are refused heart surgery. However, there is now at least one child with full Edwards Syndrome who has been given a tracheostomy in recent years and has had greatly improved health as a result.

We’ve lived with the advantages and disadvantages of that little tube for over five years now. Recently a sudden inflammation in the nose meant that for the second time ever we weren’t able to pass the tube. We were in Spain at the time and a combination of laziness and experience made us decide against taking her to hospital, instead we decided to ride the problem out at home. We attached Cali to her sats monitor and went to bed early expecting a night of little sleep and great distress from Cali. The results were better than we’d anticipated, she seemed unbothered by her tubeless nose and though her sleep was light and her heartrate was higher, she was able to sleep some of the night without constantly obstructing. This has made me hope that one day Cali will be able to manage without the tube.

If anybody reading this is considering an NPA for their child or has one already and needs any help with it, then please get in contact via the Soft contact page. I would love to be able to pass on any wisdom that might be helpful, and be something like the big sister that P has been to me.

Jay x